Post by Admin on Jul 31, 2022 12:41:01 GMT -7

In 1821 the Santa Fe Trail was established between the New Mexico trading hub at Santa Fe and the Eastern United States at St Louis.

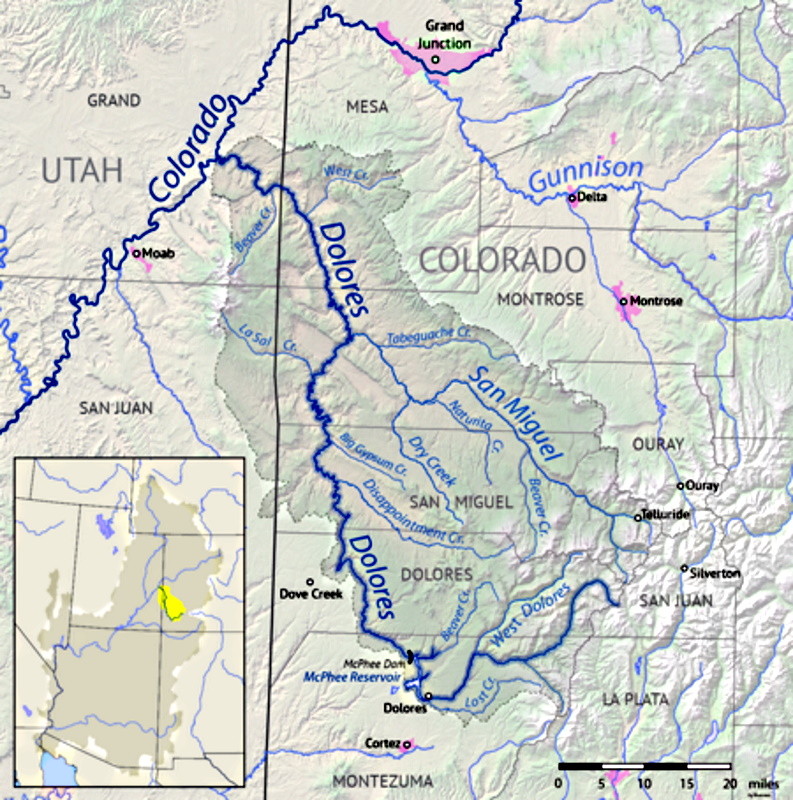

In 1829 Antonio Armijo finally found a route connecting Santa Fe to Los Angeles. The problem was getting around the Grand Canyon. Major considerations were finding passable territory and food and water for themselves and their stock along the way. They finally found it by following La Sal Creek from the Dolores River.

The Old Spanish Trail began.

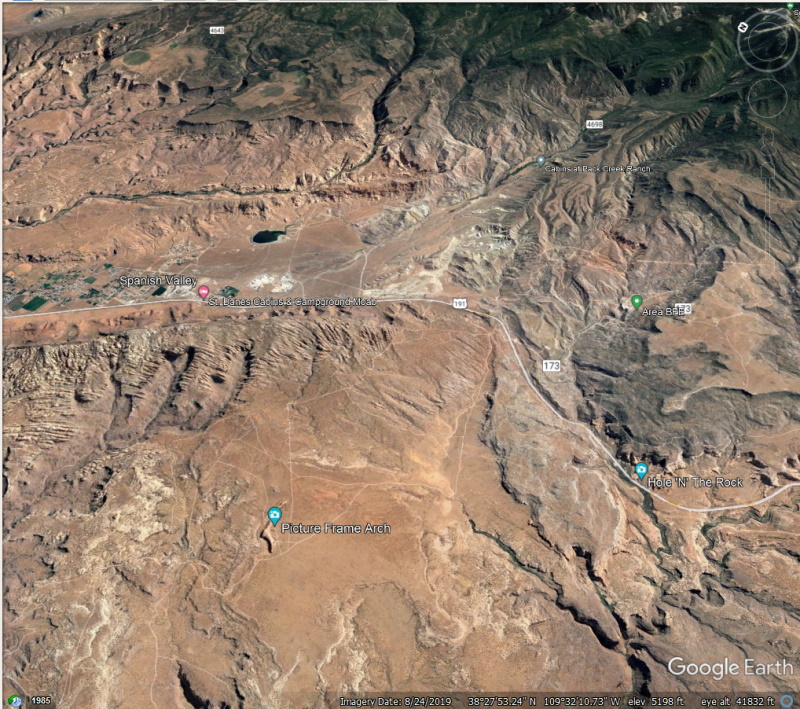

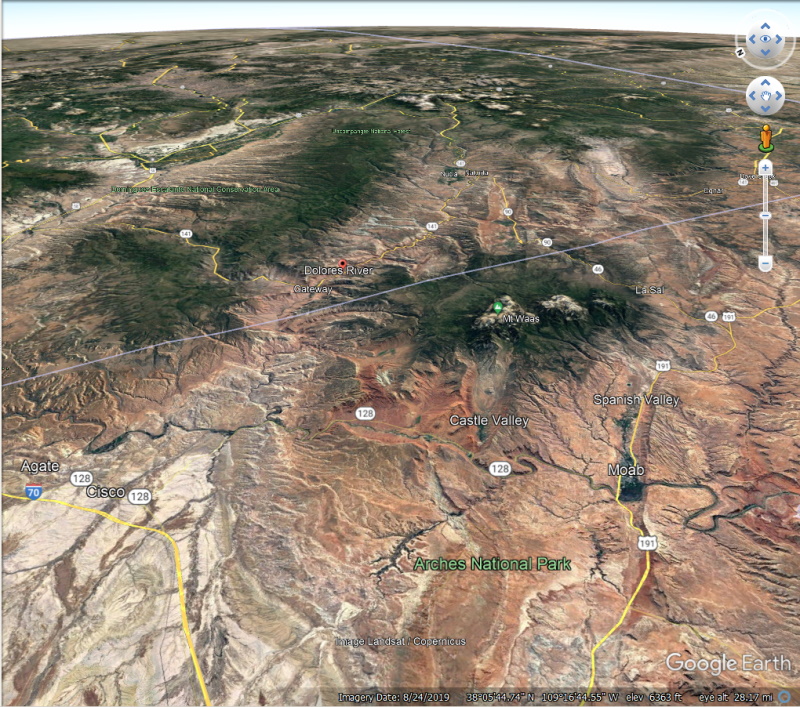

An overview of the area that finally provided passage.

One of the first stopping places in Utah was La Sal -"The Salt."

In the heat of the summer they stared up at the white mountain tops above them and couldn't imagine snow still lingered. "That must be salt!" so they named them "La Sal Montanyas," and they have been the La Sals ever since.

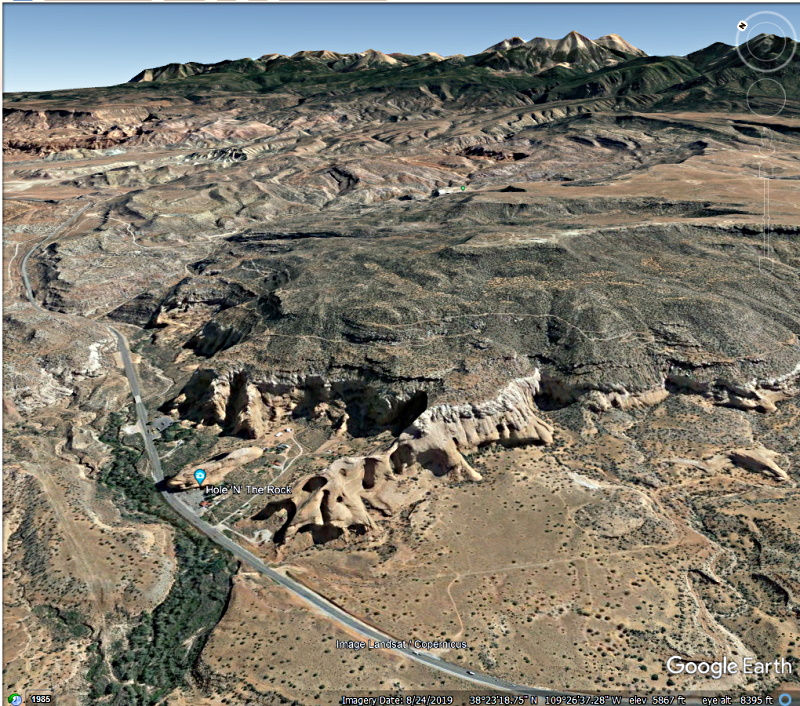

Continuing northwest possible paths were few.

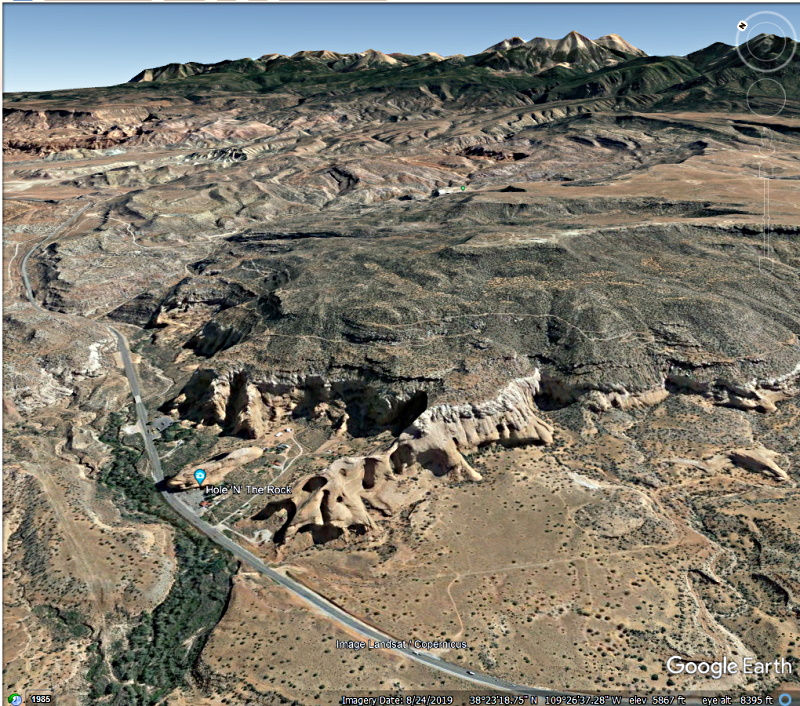

They finally discovered the "Hole in the Wall" of Butch Cassidy and Sun Dance Kid fame. Followed today by US 191.

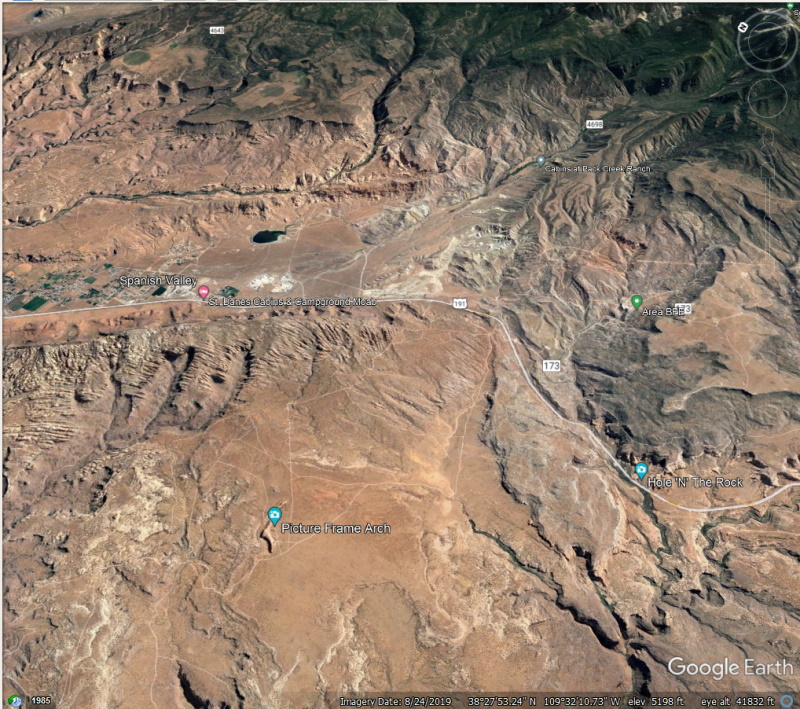

That allowed them to enter Spanish Valley.

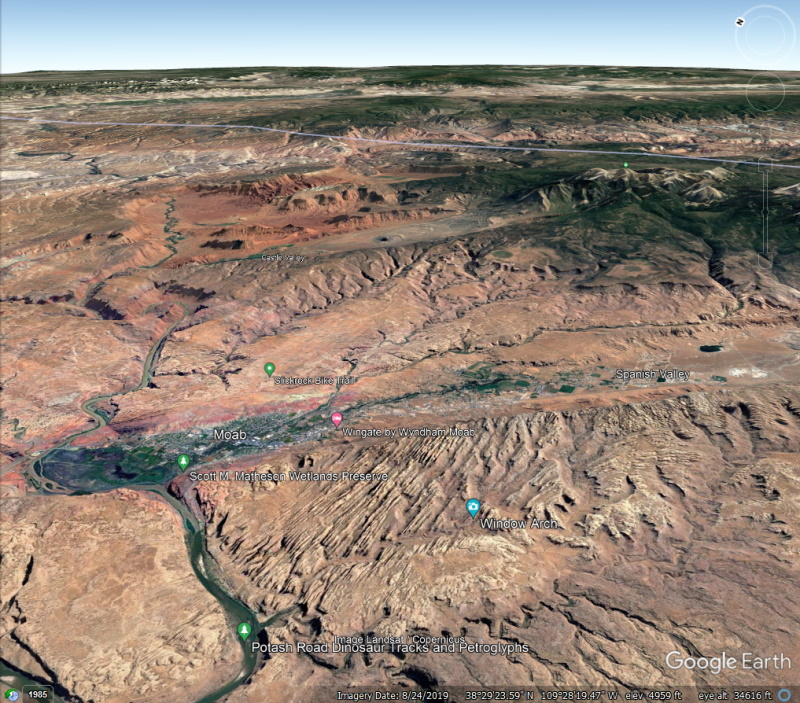

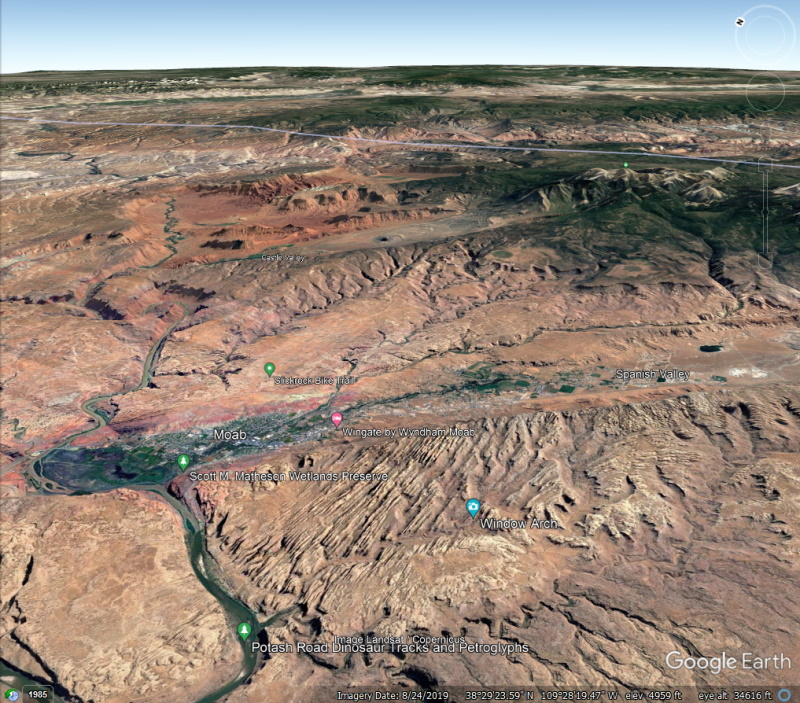

And at the present location of Moab they finally worked out a place to cross the Colorado River.

Way Back in 1756, While back east the Americans were having problems with England, Juan Maria Antonio Rivera began an expedition from Santa Fe New Mexico, supposedly trying to get to Los Angeles. Not knowing of the La Sal Creek path, he began following a river north he named “El Rio de Nuestra Senora de Dolores”- The River of Our Lady of Sorrows.

issuu.com/utah10/docs/uhq_volume60_1992_number3/s/161894

The Rivera Expedition was executed at a critical time in the history of Spain's involvement in North America, when the success or failure of the Spanish American venture would be decided. It was accomplished without force of arms; in fact, Rivera had no armed escort. It succeeded, despite the odds, on the basis of its leader's great personal courage, determination, and diplomacy with the native groups.

The Rivera Expedition consisted of two entradas: the first in June and July of 1765 and the second in October and November of the same year. The objective of the first entrada was not stated in the incomplete documents brought forth in 1975; however, in the instructions issued by Governor Tomas Velez de Cachupin for the conduct of the second entrada, reference was made to the first trip as having been one of discovery of silver and the location of the great river.

A careful reading of the authorization for the second entrada reveals the deeper intent of the expedition. Governor Cachupin directed Rivera and his companions to go disguised as traders and conceal the fact they were Spanish; to reconnoiter the land along the trail, at the crossing, and on the other side of the river; to determine the names of the nations they encountered; and to ascertain the languages of the native groups and their attitude toward the Spanish; and to make a journal account of the trip and map the trail to the crossing.

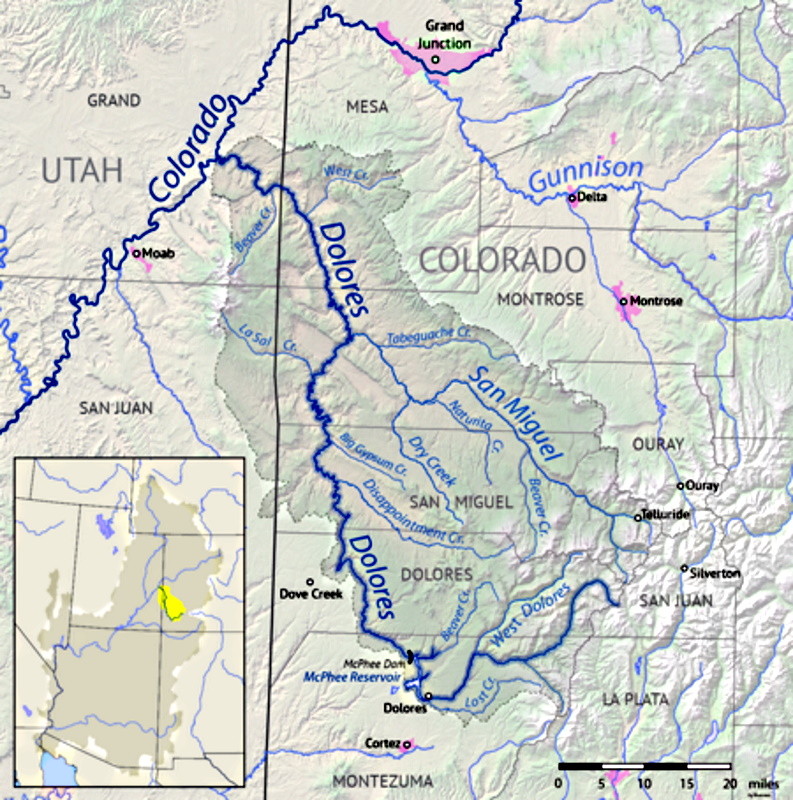

Near Egnar the river crosses into San Miguel County and then from there into Montrose County. Continuing north, the Dolores cuts across the Paradox Valley which runs in an unusual transverse direction to the river. Immediately below Paradox Valley it is joined by the San Miguel River, its main tributary, from the east. Incidentally, the Dolores and San Miguel have their headwaters on opposite sides of Lizard Head Pass.

Below the confluence with the San Miguel, the Dolores enters Mesa County, flowing north-northwest past Gateway and then turning west into Utah. The last segment of the river, entirely within Grand County, joins the Colorado near the historic Dewey Bridge, about 30 miles (48 km) above Moab.

Geology

The ancestral Dolores River is believed to have flowed south to join the San Juan River near the Four Corners in what is now northwestern New Mexico. The uplift of Sleeping Ute Mountain about 70 million years ago diverted the Dolores River to its present northward course, causing it to carve the Dolores River Canyon on its way to the Colorado River, creating unusual geologic features such as the Paradox Valley. The Dolores Canyon exposes rocks ranging from 300-million-year-old Pennsylvanian limestone to the 140-million-year-old Entrada sandstone deposited during the Jurassic. A cap of Cretaceous Dakota sandstone forms most of the upper rim of the canyon.

The lower Dolores River may have once been the original course of the Colorado River, which flowed through the now dry Unaweep Canyon, currently occupied by West Creek, a small tributary of the Dolores. When the Uncompahgre Plateau was formed it diverted the larger Colorado northwards through what is now the Grand Valley, looping around through Westwater Canyon to the confluence with the Dolores in eastern Utah and leaving Unaweep Canyon as a huge dry gap across the plateau.

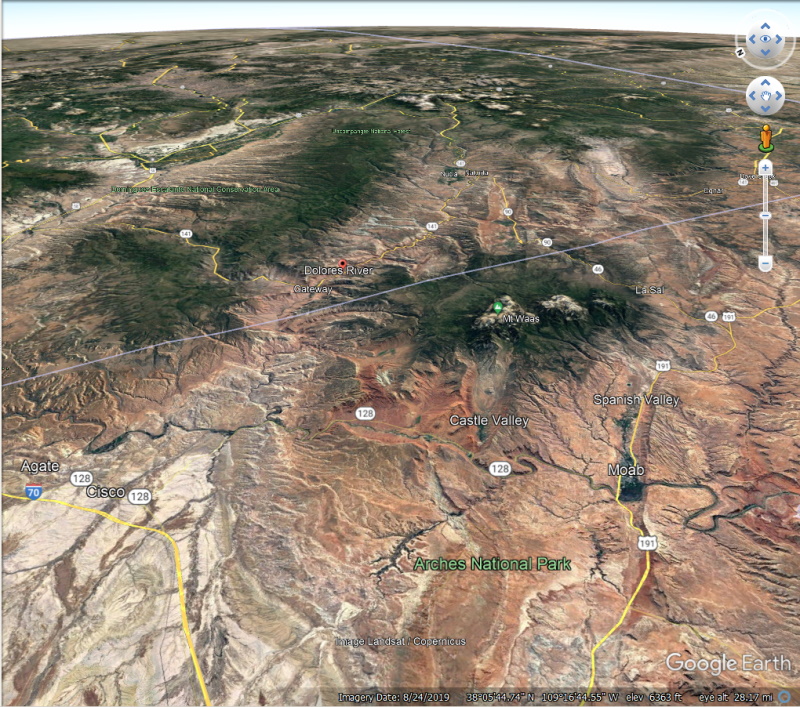

Looking up the Dolores River where it connects to the Colorado that runs down to Moab. behind Moab is Spanish Valley, another part of the Old Spanish Trail. Between the two trails are the La Sal Mountains.

Arches National Park is in the lower foreground.

In 1829 Antonio Armijo finally found a route connecting Santa Fe to Los Angeles. The problem was getting around the Grand Canyon. Major considerations were finding passable territory and food and water for themselves and their stock along the way. They finally found it by following La Sal Creek from the Dolores River.

The Old Spanish Trail began.

An overview of the area that finally provided passage.

One of the first stopping places in Utah was La Sal -"The Salt."

In the heat of the summer they stared up at the white mountain tops above them and couldn't imagine snow still lingered. "That must be salt!" so they named them "La Sal Montanyas," and they have been the La Sals ever since.

Continuing northwest possible paths were few.

They finally discovered the "Hole in the Wall" of Butch Cassidy and Sun Dance Kid fame. Followed today by US 191.

That allowed them to enter Spanish Valley.

And at the present location of Moab they finally worked out a place to cross the Colorado River.

Part 2 - The Dolores River

Way Back in 1756, While back east the Americans were having problems with England, Juan Maria Antonio Rivera began an expedition from Santa Fe New Mexico, supposedly trying to get to Los Angeles. Not knowing of the La Sal Creek path, he began following a river north he named “El Rio de Nuestra Senora de Dolores”- The River of Our Lady of Sorrows.

issuu.com/utah10/docs/uhq_volume60_1992_number3/s/161894

The Rivera Expedition was executed at a critical time in the history of Spain's involvement in North America, when the success or failure of the Spanish American venture would be decided. It was accomplished without force of arms; in fact, Rivera had no armed escort. It succeeded, despite the odds, on the basis of its leader's great personal courage, determination, and diplomacy with the native groups.

The Rivera Expedition consisted of two entradas: the first in June and July of 1765 and the second in October and November of the same year. The objective of the first entrada was not stated in the incomplete documents brought forth in 1975; however, in the instructions issued by Governor Tomas Velez de Cachupin for the conduct of the second entrada, reference was made to the first trip as having been one of discovery of silver and the location of the great river.

A careful reading of the authorization for the second entrada reveals the deeper intent of the expedition. Governor Cachupin directed Rivera and his companions to go disguised as traders and conceal the fact they were Spanish; to reconnoiter the land along the trail, at the crossing, and on the other side of the river; to determine the names of the nations they encountered; and to ascertain the languages of the native groups and their attitude toward the Spanish; and to make a journal account of the trip and map the trail to the crossing.

Near Egnar the river crosses into San Miguel County and then from there into Montrose County. Continuing north, the Dolores cuts across the Paradox Valley which runs in an unusual transverse direction to the river. Immediately below Paradox Valley it is joined by the San Miguel River, its main tributary, from the east. Incidentally, the Dolores and San Miguel have their headwaters on opposite sides of Lizard Head Pass.

Below the confluence with the San Miguel, the Dolores enters Mesa County, flowing north-northwest past Gateway and then turning west into Utah. The last segment of the river, entirely within Grand County, joins the Colorado near the historic Dewey Bridge, about 30 miles (48 km) above Moab.

Geology

The ancestral Dolores River is believed to have flowed south to join the San Juan River near the Four Corners in what is now northwestern New Mexico. The uplift of Sleeping Ute Mountain about 70 million years ago diverted the Dolores River to its present northward course, causing it to carve the Dolores River Canyon on its way to the Colorado River, creating unusual geologic features such as the Paradox Valley. The Dolores Canyon exposes rocks ranging from 300-million-year-old Pennsylvanian limestone to the 140-million-year-old Entrada sandstone deposited during the Jurassic. A cap of Cretaceous Dakota sandstone forms most of the upper rim of the canyon.

The lower Dolores River may have once been the original course of the Colorado River, which flowed through the now dry Unaweep Canyon, currently occupied by West Creek, a small tributary of the Dolores. When the Uncompahgre Plateau was formed it diverted the larger Colorado northwards through what is now the Grand Valley, looping around through Westwater Canyon to the confluence with the Dolores in eastern Utah and leaving Unaweep Canyon as a huge dry gap across the plateau.

Looking up the Dolores River where it connects to the Colorado that runs down to Moab. behind Moab is Spanish Valley, another part of the Old Spanish Trail. Between the two trails are the La Sal Mountains.

Arches National Park is in the lower foreground.

When Albert Charles Peale surveyed the valley in 1875, he found that the geography caused the Dolores River flowing through it to preform strange and unexpected things. Instead of a parallel course as is most often taken by rivers, the river chose to take a perpendicular course through the valley. He chose the name Paradox This paradox of fluvial geomorphology gave the place its name, Paradox Valley. The name “Paradox” was later applied to other geologic structures in the area.